SCIENCE

According to this new research, the Venus flytrap can. . . count? (Washington Post)

Take a walk on the Flytrap Trail with our short article.

Teachers, scroll down for a quick list of key resources in our Teachers’ Toolkit.

Discussion Ideas

- The Venus flytrap has a very tiny natural species range. Where is it? Read through our short article, “Plant Predators,” for some help.

- Venus flytraps are only found naturally in the wetlands of the Carolinas. (The Flytrap Trail, where our article is set, is part of Carolina Beach State Park, North Carolina.)

- Assistant Park Ranger A.J. Loomis explains: “It’s naturally growing here for one reason: The soil is so poor.” The flytrap digests insects to supplement the low amount of nitrogen and phosphorus it receives from the region’s sandy, acidic soil.

- Venus flytraps are only found naturally in the wetlands of the Carolinas. (The Flytrap Trail, where our article is set, is part of Carolina Beach State Park, North Carolina.)

Illustration by Jenny Wang, National Geographic

- How does a Venus flytrap catch its prey? Read through our short article, “Plant Predators,” for some help.

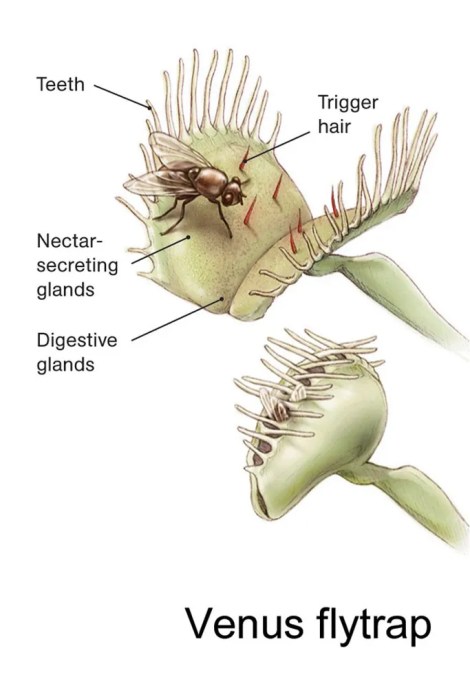

- The plant’s “trap” is a single, foldable leaf with trigger hairs. When a fly or ant brushes against one of the leaf’s trigger hairs two times, the plant folds its leaf quickly, trapping the prey inside. Then, the Venus flytrap secretes a digestive fluid that helps the plant absorb nutrients from the trapped insect. It takes three to five days for the plant to digest the insect. Each leaf-trap can open and close about three times before dying and falling off the plant. The old trap is replaced by a new one from the Venus flytrap’s underground stems.

- Watch the video above, part of new research into how Venus flytraps catch their prey. The research measured “action potentials” as trigger hairs on the Venus flytrap were stimulated. What are action potentials?

- Action potentials are electrical changes that occur in a cell when it is stimulated. Our own cells undergo millions of action potentials every day. In muscle cells, action potentials signal a muscle to contract. In neurons, action potentials are known as “nerve impulses” and help us react very quickly to stimuli. “For example, if you burn your fingers it is important that your brain gets the message to withdraw your hand very quickly.”

- A Venus flytrap’s action potentials triggered by a one-touch stimulus, two-touch stimulus, and three-touch stimulus are very different. What reactions are triggered by each stimulus? Watch the video or read the Washington Post article for some help.

- 1-touch: According to the Washington Post, “one touch set the flytraps into high-alert mode—but didn’t actually result in any action on the plant’s part.” Scientists think this is a handy adaptation that the Venus flytrap developed to help it avoid exerting energy snapping its trap at a raindrop or wispy dandelion fluff that drifts by.

- 2-touch: “If a second touch happened within a few seconds, the trap snaps partially shut.”

- 3+-touch: “The trap shuts all the way after more touches, and the fifth touch triggered the release of digestive enzymes. After that, more touches mean more digestive enzymes. This allows the plant to expend just enough energy to successfully subdue and consume its prey: A bigger, livelier insect will get more attention as it struggles than a weak bug.”

- In the words of Nat Geo blogger Ed Yong, “The plant apportions its digestive efforts according to the struggles of its prey. And the fly, by fighting for its life, tells the plant to start killing it, and how vigorously to do so.”

- Cue the video to about 1:08 to see the struggling insect drown as “the plant turns into a green stomach.”

Photograph by Paul Zahl, National Geographic

TEACHERS’ TOOLKIT

Washington Post: The Venus flytrap has a really creepy trick for catching its prey

Nat Geo: Plant Predators

(extra credit!) Current Biology: The Venus Flytrap Dionaea muscipula Counts Prey-Induced Action Potentials to Induce Sodium Uptake

Excellent article, I love reading about venus flytraps – I’ve been fascinated with them for some time now. I’ve composed some interesting venus flytrap content myself (http://venusflytrapfacts.com).

Is it autotroph or heterotroph? Or any other.

Great question, Chander!

Venus flytraps and other carnivorous plants are autotrophs. They have heterotrophic qualities, but their carnivorous consumption only supplements their regular plant-diet of nutrients. Venus flytraps can successfully “go vegan.”

Let the good folks at at the International Carnivorous Plant Society tell you all about it!